Bazaar of Generations

The sign above the door at 11 Bowbazaar Street still said "I.S. Musleah," my grandfather’s name, and up in the dark, musty staircase began the journey for which I had traveled over 7,000 miles from Great Neck, New York. After 33 years, I had returned to Calcutta, where I was born. The only member of my family left at 11 Bowbazaar was my great-aunt Ramah, 89, bedridden after a fall. As a child of six, I had emigrated to the United States with my parents and two sisters, leaving behind the city that had been home to my family since 1820, when Hakham Eliahu Musleah, grandson of the chief rabbi of Baghdad, settled in Calcutta. What I remembered was a hazy reconstruction of old photographs and family stories, fueled by imagination and buffeted by images of squalor and homelessness. But the desire to return had remained constant.I traveled back with my parents in February 1997. Unaccompanied by a husband or my two children, I was often mistaken for a girl of 20 instead of a woman of 39. I slept in the bed in which my father was born. I sat in my grandfather’s seat in the Maghen David Synagogue, next to my father, who sat in his grandfather’s seat. Back at 11 Bowbazaar, I listened to the clock chime every quarter hour and imagined my grandmother listening to the same chimes-the grandmother I had never met, the grandmother after whom I had named my daughter Shoshana.

For me it was a dream fulfilled, a journey back to the place where much of my family history began and the paths upon which I and my children now tread were set by personalities and character and circumstance. The reality I found was not lyrical or lovely. Instead, it bordered on a shattering sense of closure not only for my family but for the Jewish community that had once numbered 5,000 and had faded to 50 elderly people. It was wretchedness and wonder combined, the bittersweet marvel of grand, granite-pillared synagogues that stood empty.

When I first climbed up the stairs at 11 Bowbazaar, kissed the mezuza and entered the house, the mixture of awe and despair was almost overwhelming. There was the south veranda where my great-grandmother peeled vegetables, and the north veranda graced by the sukka on Sukkot. Here was the godown - the storage pantry - my father sneaked into as a child to savor the secret taste of biscuits and sweets. This was the window my grandmother looked out in anguish after giving birth to a stillborn child. It was jolting to stand in the places the stories had occurred, as if mythology had sprung to life.

I wondered around the dark rooms filled with heavy rosewood furniture, stared up at the peeling walls and the old-fashioned light switches. My own wedding photo faced those of my aunts and grandparents, mirror images. The sense of continuity at being in a place that breathed generations was eerie.

The cold, hard details of living at 11 Bowbazaar for a week brought me down to earth. I gawked at the gray stone bathroom where I was told I could bathe by mixing hot and cold water in a small steel tub and pouring the combination over myself with a bucket. The toilet, in a separate room, jammed up if paper was thrown in. Paper or not, it usually didn’t flush at all. I lay down on the bed, shrouded in a mosquito net with moth-eaten holes that defeated its purpose. With my head on a pillow as hard as the rock Jacob lay on when he dreamed of angels, I made peace with the fact that amenities wouldn’t be the strong point of the trip.

We found other treasures to compensate. Aunty Ramah was surrounded by a handful of loyal caregivers. Chief among them was the trustworthy cook, waiter and butler rolled into one whom Aunty Ramah calls, "Boy!" because she’s known him since he was a "table boy" who assisted the cook and did odd jobs around the house.

"What is his real name?" I wanted to know. "Apka nam kya hai?" my mother instructed me to ask in Hindustani, a colloquial dialect of Hindi. "Suleiman," he answered with a smile.

Every morning Suleiman served us tea in butter-yellow cups and saucers, and whatever fresh sweets or savories he’d just bought: crisp, fried, puffed kachowris with potato curry; sweet whole-milk yogurt that came in a clay pot; creamy Indian sweets in tempting arrays; heart-shaped "queen cakes" from Nahoum’s, the Jewish-owned bakery. Every morning my mother would chat in Hindustani with Suleiman, going over the menu for the day. He cooked us lunches and dinners: a potato and egg dish called mahmoosa; curries of minced vegetables that melted into subtle stews; dal (lentils) and rice; even handmade potato chips!

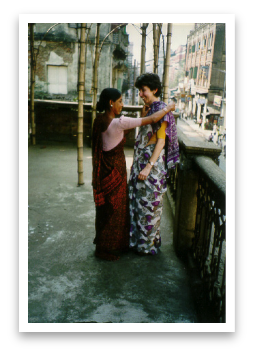

Muni, the cheerful ayah (nursemaid) who bathed and dressed and fed Aunty Ramah, adopted me. With my mother as translator, she told me about her shadhi, her arranged marriage – and how embarrassed she had been when she met her husband for the first time at her wedding. She tried teaching me some Hindi, and I repeated after her haltingly: Apko America may yad karega: "I’ll remember you in America." On my own, I added: Bahot acha: "Okay, good," wagging my head from side to side in the Indian manner. She draped me in her saris, pasted red beauty dots – bindis – on my forehead and giggled at the results.

My father guided me through the old Jewish neighborhoods. "This is where I was getting my hair cut when the Hindu-Muslim riots started in 1946," he remembered at one spot. "I had to run home with only half my hair done… This is Norton Buildings, where my father worked for 37 years." Or, opening a gate, "My Hebrew master used to live in this one room with his six children."

The vendors in the street filled my senses with a rich feast of sights and smells of the foods they peddled. They fried eggs on clay stoves; boiled milk and tea sweetened with plenty of sugar and sold it for one rupee (3 cents) in tiny clay cups; shaved a block of ice and poured syrup over the ice chips in a glass. My mother stood fascinated at the snack stalls, trying to discern the secrets of the perfect golden pakoras – slices of eggplant and onion coated in chickpea flour and deep-fried. At home she used minuscule portions of oil, salt and sugar in her cooking, but here she craved spicy salted chickpeas; doughy, deep-fried pitchkas dipped in hot sauce, and fudgy paeras.

Not all the sights were as appetizing. Outside 8/81 Bentinck Street, where my family lived before we left for America, men used a wall as a urinal. I immediately began to walk looking down. The rickshaw wallahs, though officially banned from the streets, beckoned for business anyway. Two men balancing a wooden door between them on their heads claimed the right of way. A beggar woman with a scrawny child on her hip opened her hand for money. As soon as I gave her one rupee I was surrounded by others and quickly learned a lesson in hardening my heart.

We stopped at Beth-El, the 140-year-old synagogue my mother’s family had attended. "So many people used to come to synagogue they used to fight for seats," she sobbed with uncharacteristic sentimentality, usually my father’s domain. "All gone. All empty." Only a handful of men now make up the Shabbat minyan.

At Maghen David, our next stop, my father’s cache of nostalgia tumbled out. Not only did he grow up in this synagogue, but when he returned to India after being ordained at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, he served as rabbi here for 12 years. Standing at the tzedaka box in the back of the sanctuary, he recalled that on every birthday his grandfather would bring him to drop in coins. The money was sent to Jerusalem, Safed, Hebron and Tiberias.

We climbed the stairs to the women’s gallery and he remembered that the last time he had been there was almost 60 years ago. He had kissed his mother’s hand after he read the maftir portion from the Torah for the first time at the age of 10. She died a month later. Hard-hearted, I made him repeat the story into the tape recorder and the video camera.

On Shabbat we returned to Maghen David, walking together to the 6 o’clock service in the dim morning light. Sitting in my grandfather’s seat, I closed my eyes and tried to feel his presence but I didn’t feel anything. I had never met him. I got up and stood behind one of the pillars, trying to imagine the benches full of people. In my mind, I pasted my grandfather’s picture onto his seat, a photograph I have of him with a kippa on his head and a siddur in his hand. I pasted my great-grandfather’s picture onto his seat, his long beard flowing, and my father’s picture as a boy onto his. Then I started to cry.

All I could do was paste pictures of people I had never known into their appropriate spots in this synagogue that was once vibrant and alive. What sadness for my father to sit and walk where in his bones, in his heart and soul, he felt the closeness of everyone he loved-all dead now. I asked him if he saw them. "It’s very vivid," he said. "It’s very hard."

When my father went up to the teba (bima) to lead Shaharit, I listened to his chanting mix with the cawing of crows and chirping of sparrows that flew in the open windows, and I suddenly and intensely wanted an aliya. I wanted to be part of the chain of melody-makers in the synagogue. Every verse decorating the arches on each side of the synagogue declared in Hebrew, "I will sing to God," or a variation of the verse. My voice, I thought, should echo and bounce off the high ceiling and up to the balcony where my grandmother and my aunts sat, looking down. I wanted to make the magnificent dying edifice mine in some small way.

I knew it wasn’t the synagogue’s custom to give women aliyot, but I asked the man in charge if there were any chance I could have one. Unwilling to take sole responsibility for the decision, he polled two or three of the 12 men present, who shook their heads no. I shrugged it off (so I thought) and went to sit with my mother in the women’s gallery, near the stained-glass windows that threw colors onto the plain benches. As I listened to my father read from the Torah about the priest’s breastplate, its colorful glowing and ornate stones worn over the heart, it seemed as if the synagogue was the breastplate, worn over my father’s heart. I wanted to wear it over mine while I was here, to show that this synagogue had a living legacy. I didn’t have the chance.

My tenuous connections to grandparents I only knew through my father’s memories were revitalized when we visited their graves. We went to the Calcutta Jewish Cemetery with a guide provided by the India Tourist Office. The caretaker opened the rusted iron gates to reveal a grassy expanse crowded with 3,000 tombs that sprouted like a forest of blackened stone coffins above the ground. My father headed straight for his parents’ graves, which he had visited only twice previously in the last 30 years.

He fell on his father’s grave, heaved one sob and kissed the stone. He fell on his mother’s grave and kissed the stone. A weed caught his attention and he plucked it. Then he straightened and recited the hashkaba, the Sefardic memorial prayer and Eishet Hayil, the selection from Proverbs praising "a woman of valor." The sound of ever-present crows mixed in eerily with the murmur of prayer.

My mother’s parents are buried in England. Standing in the background, she explained the poignancy of the moment to the guide. "His mother died when she was just 39," she whispered, but her words shocked me as if she had blared them through a loudspeaker. Was it an accident that I was kissing my grandmother’s grave for the first time at the same age at which she had died?

After my father washed his hands, the ritual ceremony upon leaving the cemetery, I hugged him and asked, "Are you okay?" He answered, "Continuity is a great thing."

One more journey on the nostalgic path home remained, a trip to Madhupur, enshrined in our memories as an idyllic hill village famous for its pure water and clear air. Since my father’s boyhood, numerous members of the Jewish community had spent vacations there. I was eager because I, too, had vivid memories of Madhupur, especially of the pet goat I adopted from among the stray animals in the village, and of horse-and-buggy rides to the ravines, the closest we came to the beach.

We boarded the five-hour Toofan Express at Howrah Station, Calcutta’s cavernous railroad mecca, and whooshed past dhobis washing clothes in ponds; fertile rice paddies; bullocks plowing fields and cows grazing. Silhouettes of palm trees waved like the blades of a windmill; the fringed leaves of banana trees looked as if they had been cut with scissors. Dung cakes dried on the railroad tracks; elaborate creations were stacked in beehive shapes.

Along the way, my father was transformed into a boy, mesmerized by the sound, movement and adventure of the train. As a child, he knew the train schedules and stations by heart, and still rattled them off: Liluah, Belur, Bally, Burdwan, Asansole. He recalled how his father used to love to put his head out the window of the train to see the old-fashioned steam engine working; how by the end of the trip his face would be black with soot.

Nothing prepared us for the disappointment in Madhupur. At first, my father didn’t see the reality— its ordinariness, a village like any other, with trash-filled dirt streets. Lost in another world, he pointed out "Home," a once-grand house whose red façade had now faded into a mottled pink. My father pulled out a tiny black-and-white picture of himself as a boy standing in front of the splendidly kept "Home" and held it up the building, almost as proof that the good old days of his childhood had indeed existed. He chatted with the Muslim family that lived there, and showed them the picture. They marveled that after 35 years he had come so far, ostensibly seeking buildings. They didn’t grasp that "Home" meant something as deep as its name.

The Dak Bungalow crushed his expectations. It had housed the British government court and guests, and fulfilled the same purpose for the Indian government. Instead of a magnificent pure-white cottage surrounded by an open green park, we found a dilapidated mustard building in the midst of a yellowed field bordered with squatters’ lean-tos. Elias Lodge, another estate, was overrun by weeds, its front gate blocked by twisted trees. In the market area, the Burdwan Sweet Shop, of blessed memory, which once sold such rich, creamy confections that people would bring boxes of sweets back to Calcutta, now attracted more flies than customers.

The one bright spot was Lilly Ville, where we stayed during our last vacation. The Anglo-Indian couple who lived there invited us inside, and when I saw the wide red veranda, it all came back to me. I remembered that was where my goat urinated and my mother banished him from the house.

We did take a buggy ride, although we didn’t have time to go as far as the ravines. We all crammed into a bicycle rickshaw that could comfortably seat two, my mother on my father’s lap. That provoked hysterical giggles, especially when we narrowly escaped being impaled on the horns of a cow in no hurry to cross the road. We haggled for clay toys, bananas, bangles and bindis, even for the price of our room at the Madhupur Rest House, until we realized we were bargaining for the equivalent of 30 cents off the two dollars it was going to cost per room. We laughed a lot during the day we spent in Madhupur, mostly because if we didn’t we probably would have dissolved in tears.

We saved those tears for the day we left Calcutta. "See you again, Aunt Ra," we promised, kissing her wistful face, wondering if we’d ever really return. But as I walked back down the musty staircase that just a few days earlier had been so dark and still, I felt it suddenly come alive with new memories of my own.

"What is his real name?" I wanted to know. "Apka nam kya hai?" my mother instructed me to ask in Hindustani, a colloquial dialect of Hindi. "Suleiman," he answered with a smile.

Every morning Suleiman served us tea in butter-yellow cups and saucers, and whatever fresh sweets or savories he’d just bought: crisp, fried, puffed kachowris with potato curry; sweet whole-milk yogurt that came in a clay pot; creamy Indian sweets in tempting arrays; heart-shaped "queen cakes" from Nahoum’s, the Jewish-owned bakery. Every morning my mother would chat in Hindustani with Suleiman, going over the menu for the day. He cooked us lunches and dinners: a potato and egg dish called mahmoosa; curries of minced vegetables that melted into subtle stews; dal (lentils) and rice; even handmade potato chips!

Muni, the cheerful ayah (nursemaid) who bathed and dressed and fed Aunty Ramah, adopted me. With my mother as translator, she told me about her shadhi, her arranged marriage – and how embarrassed she had been when she met her husband for the first time at her wedding. She tried teaching me some Hindi, and I repeated after her haltingly: Apko America may yad karega: "I’ll remember you in America." On my own, I added: Bahot acha: "Okay, good," wagging my head from side to side in the Indian manner. She draped me in her saris, pasted red beauty dots – bindis – on my forehead and giggled at the results.

My father guided me through the old Jewish neighborhoods. "This is where I was getting my hair cut when the Hindu-Muslim riots started in 1946," he remembered at one spot. "I had to run home with only half my hair done… This is Norton Buildings, where my father worked for 37 years." Or, opening a gate, "My Hebrew master used to live in this one room with his six children."

The vendors in the street filled my senses with a rich feast of sights and smells of the foods they peddled. They fried eggs on clay stoves; boiled milk and tea sweetened with plenty of sugar and sold it for one rupee (3 cents) in tiny clay cups; shaved a block of ice and poured syrup over the ice chips in a glass. My mother stood fascinated at the snack stalls, trying to discern the secrets of the perfect golden pakoras – slices of eggplant and onion coated in chickpea flour and deep-fried. At home she used minuscule portions of oil, salt and sugar in her cooking, but here she craved spicy salted chickpeas; doughy, deep-fried pitchkas dipped in hot sauce, and fudgy paeras.

Not all the sights were as appetizing. Outside 8/81 Bentinck Street, where my family lived before we left for America, men used a wall as a urinal. I immediately began to walk looking down. The rickshaw wallahs, though officially banned from the streets, beckoned for business anyway. Two men balancing a wooden door between them on their heads claimed the right of way. A beggar woman with a scrawny child on her hip opened her hand for money. As soon as I gave her one rupee I was surrounded by others and quickly learned a lesson in hardening my heart.

We stopped at Beth-El, the 140-year-old synagogue my mother’s family had attended. "So many people used to come to synagogue they used to fight for seats," she sobbed with uncharacteristic sentimentality, usually my father’s domain. "All gone. All empty." Only a handful of men now make up the Shabbat minyan.

At Maghen David, our next stop, my father’s cache of nostalgia tumbled out. Not only did he grow up in this synagogue, but when he returned to India after being ordained at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, he served as rabbi here for 12 years. Standing at the tzedaka box in the back of the sanctuary, he recalled that on every birthday his grandfather would bring him to drop in coins. The money was sent to Jerusalem, Safed, Hebron and Tiberias.

We climbed the stairs to the women’s gallery and he remembered that the last time he had been there was almost 60 years ago. He had kissed his mother’s hand after he read the maftir portion from the Torah for the first time at the age of 10. She died a month later. Hard-hearted, I made him repeat the story into the tape recorder and the video camera.

On Shabbat we returned to Maghen David, walking together to the 6 o’clock service in the dim morning light. Sitting in my grandfather’s seat, I closed my eyes and tried to feel his presence but I didn’t feel anything. I had never met him. I got up and stood behind one of the pillars, trying to imagine the benches full of people. In my mind, I pasted my grandfather’s picture onto his seat, a photograph I have of him with a kippa on his head and a siddur in his hand. I pasted my great-grandfather’s picture onto his seat, his long beard flowing, and my father’s picture as a boy onto his. Then I started to cry.

All I could do was paste pictures of people I had never known into their appropriate spots in this synagogue that was once vibrant and alive. What sadness for my father to sit and walk where in his bones, in his heart and soul, he felt the closeness of everyone he loved-all dead now. I asked him if he saw them. "It’s very vivid," he said. "It’s very hard."

When my father went up to the teba (bima) to lead Shaharit, I listened to his chanting mix with the cawing of crows and chirping of sparrows that flew in the open windows, and I suddenly and intensely wanted an aliya. I wanted to be part of the chain of melody-makers in the synagogue. Every verse decorating the arches on each side of the synagogue declared in Hebrew, "I will sing to God," or a variation of the verse. My voice, I thought, should echo and bounce off the high ceiling and up to the balcony where my grandmother and my aunts sat, looking down. I wanted to make the magnificent dying edifice mine in some small way.

I knew it wasn’t the synagogue’s custom to give women aliyot, but I asked the man in charge if there were any chance I could have one. Unwilling to take sole responsibility for the decision, he polled two or three of the 12 men present, who shook their heads no. I shrugged it off (so I thought) and went to sit with my mother in the women’s gallery, near the stained-glass windows that threw colors onto the plain benches. As I listened to my father read from the Torah about the priest’s breastplate, its colorful glowing and ornate stones worn over the heart, it seemed as if the synagogue was the breastplate, worn over my father’s heart. I wanted to wear it over mine while I was here, to show that this synagogue had a living legacy. I didn’t have the chance.

My tenuous connections to grandparents I only knew through my father’s memories were revitalized when we visited their graves. We went to the Calcutta Jewish Cemetery with a guide provided by the India Tourist Office. The caretaker opened the rusted iron gates to reveal a grassy expanse crowded with 3,000 tombs that sprouted like a forest of blackened stone coffins above the ground. My father headed straight for his parents’ graves, which he had visited only twice previously in the last 30 years.

He fell on his father’s grave, heaved one sob and kissed the stone. He fell on his mother’s grave and kissed the stone. A weed caught his attention and he plucked it. Then he straightened and recited the hashkaba, the Sefardic memorial prayer and Eishet Hayil, the selection from Proverbs praising "a woman of valor." The sound of ever-present crows mixed in eerily with the murmur of prayer.

My mother’s parents are buried in England. Standing in the background, she explained the poignancy of the moment to the guide. "His mother died when she was just 39," she whispered, but her words shocked me as if she had blared them through a loudspeaker. Was it an accident that I was kissing my grandmother’s grave for the first time at the same age at which she had died?

After my father washed his hands, the ritual ceremony upon leaving the cemetery, I hugged him and asked, "Are you okay?" He answered, "Continuity is a great thing."

One more journey on the nostalgic path home remained, a trip to Madhupur, enshrined in our memories as an idyllic hill village famous for its pure water and clear air. Since my father’s boyhood, numerous members of the Jewish community had spent vacations there. I was eager because I, too, had vivid memories of Madhupur, especially of the pet goat I adopted from among the stray animals in the village, and of horse-and-buggy rides to the ravines, the closest we came to the beach.

We boarded the five-hour Toofan Express at Howrah Station, Calcutta’s cavernous railroad mecca, and whooshed past dhobis washing clothes in ponds; fertile rice paddies; bullocks plowing fields and cows grazing. Silhouettes of palm trees waved like the blades of a windmill; the fringed leaves of banana trees looked as if they had been cut with scissors. Dung cakes dried on the railroad tracks; elaborate creations were stacked in beehive shapes.

Along the way, my father was transformed into a boy, mesmerized by the sound, movement and adventure of the train. As a child, he knew the train schedules and stations by heart, and still rattled them off: Liluah, Belur, Bally, Burdwan, Asansole. He recalled how his father used to love to put his head out the window of the train to see the old-fashioned steam engine working; how by the end of the trip his face would be black with soot.

Nothing prepared us for the disappointment in Madhupur. At first, my father didn’t see the reality— its ordinariness, a village like any other, with trash-filled dirt streets. Lost in another world, he pointed out "Home," a once-grand house whose red façade had now faded into a mottled pink. My father pulled out a tiny black-and-white picture of himself as a boy standing in front of the splendidly kept "Home" and held it up the building, almost as proof that the good old days of his childhood had indeed existed. He chatted with the Muslim family that lived there, and showed them the picture. They marveled that after 35 years he had come so far, ostensibly seeking buildings. They didn’t grasp that "Home" meant something as deep as its name.

The Dak Bungalow crushed his expectations. It had housed the British government court and guests, and fulfilled the same purpose for the Indian government. Instead of a magnificent pure-white cottage surrounded by an open green park, we found a dilapidated mustard building in the midst of a yellowed field bordered with squatters’ lean-tos. Elias Lodge, another estate, was overrun by weeds, its front gate blocked by twisted trees. In the market area, the Burdwan Sweet Shop, of blessed memory, which once sold such rich, creamy confections that people would bring boxes of sweets back to Calcutta, now attracted more flies than customers.

The one bright spot was Lilly Ville, where we stayed during our last vacation. The Anglo-Indian couple who lived there invited us inside, and when I saw the wide red veranda, it all came back to me. I remembered that was where my goat urinated and my mother banished him from the house.

We did take a buggy ride, although we didn’t have time to go as far as the ravines. We all crammed into a bicycle rickshaw that could comfortably seat two, my mother on my father’s lap. That provoked hysterical giggles, especially when we narrowly escaped being impaled on the horns of a cow in no hurry to cross the road. We haggled for clay toys, bananas, bangles and bindis, even for the price of our room at the Madhupur Rest House, until we realized we were bargaining for the equivalent of 30 cents off the two dollars it was going to cost per room. We laughed a lot during the day we spent in Madhupur, mostly because if we didn’t we probably would have dissolved in tears.

We saved those tears for the day we left Calcutta. "See you again, Aunt Ra," we promised, kissing her wistful face, wondering if we’d ever really return. But as I walked back down the musty staircase that just a few days earlier had been so dark and still, I felt it suddenly come alive with new memories of my own.